Let us imagine a straight line: an interactive installation program note

Let us imagine a straight line is an interactive work about movement, the first installment in my ongoing project for dancer, video, music, and live electronics called Studies in Movement. I take my titles from two French thinkers of the late 19th century: physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey and philosopher Henri Bergson. Marey conceived the apparatus for the modern scientific study of movement. He invented instruments to measure human and animal locomotion—a beating heart, a bird in flight—and developed technologies that eventually led to the modern cinema. Bergson responded to these advances with a philosophy that rethought the relation between space and time, matter and memory, physical and psychical movement. The counterpoint of Bergson’s thought and Marey’s vision suggests a drama about the power and limits of human perception. Where Marey saw discrete temporal units on grids and graphs, Bergson saw an irreducible continuity in metaphysical space. Let us imagine a straight line invites participants to experience the difference between these ways of seeing and then to decide for themselves.

Let us imagine a straight line is an interactive work about movement, the first installment in my ongoing project for dancer, video, music, and live electronics called Studies in Movement. I take my titles from two French thinkers of the late 19th century: physiologist Etienne-Jules Marey and philosopher Henri Bergson. Marey conceived the apparatus for the modern scientific study of movement. He invented instruments to measure human and animal locomotion—a beating heart, a bird in flight—and developed technologies that eventually led to the modern cinema. Bergson responded to these advances with a philosophy that rethought the relation between space and time, matter and memory, physical and psychical movement. The counterpoint of Bergson’s thought and Marey’s vision suggests a drama about the power and limits of human perception. Where Marey saw discrete temporal units on grids and graphs, Bergson saw an irreducible continuity in metaphysical space. Let us imagine a straight line invites participants to experience the difference between these ways of seeing and then to decide for themselves.

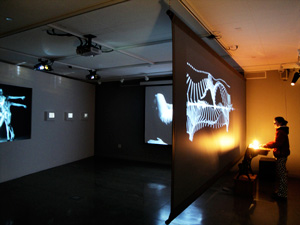

The work is made of five pieces, staged on four walls. It begins at the building’s entrance, on the west wall, with a sculpture of moving light. As an entry point, the piece presents a crossroads, marking the difference between outside and inside. The vertical bars and the points of light suggest an analogy to Marey’s grids, while the continuous movement anticipates Bergson’s question about the way the light may or may not imagine itself: would it assume the form of a line?

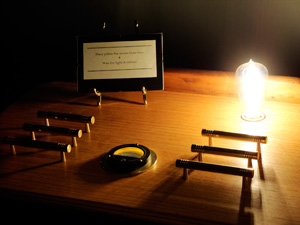

Another entrance, through a door on the opposite wall, leads to the second piece and the central space of the installation. A handcrafted machine—an antique EKG of my own design—stands inside the doorway, recalling the precision and artisanship of the instruments created during the heyday of the scientific revolution. My machine imaginatively combines, in fact, two of Marey’s most celebrated inventions: the sphygmograph, which defined the field of modern cardiology by producing the first graphical records of pulse; and the chronophotograph, which anticipated the modern cinema by producing the first multiple exposures on single glass plates and on film. Viewers activate the installation by placing their hands on the EKG: at the moment the heart rate is calculated, a moving body springs to life, leaving a trail of exposures that animates the corridor screen.

Another entrance, through a door on the opposite wall, leads to the second piece and the central space of the installation. A handcrafted machine—an antique EKG of my own design—stands inside the doorway, recalling the precision and artisanship of the instruments created during the heyday of the scientific revolution. My machine imaginatively combines, in fact, two of Marey’s most celebrated inventions: the sphygmograph, which defined the field of modern cardiology by producing the first graphical records of pulse; and the chronophotograph, which anticipated the modern cinema by producing the first multiple exposures on single glass plates and on film. Viewers activate the installation by placing their hands on the EKG: at the moment the heart rate is calculated, a moving body springs to life, leaving a trail of exposures that animates the corridor screen.

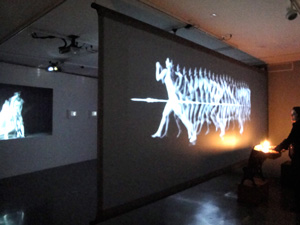

The movies feature the image of the South African dancer Ami Shulman, who has been my close collaborator throughout this project, and who can be seen walking, running, leaping, and dancing in all of the pieces that make up the installation. The different ways in which her body is presented reflect the different visions of my two protagonists. On the one hand, we see her graceful movements broken down and analyzed, in much the same way that Marey analyzed his experimental subjects at the Station physiologique outside Paris. On the other hand, we see the same movements as more complex visual events, whose irreducibility suggests the absolute continuity that Bergson posited as the basis of all movement.

An angled wall facing the entry corridor offers a window that allows participants to look into the dancer’s body and “read” it with their own gestures. A connecting wall bridges the two worlds, offering a sensual close-up that echoes the visual display at the entrance of the building. Here, the dancer’s body forms an arresting centerpiece for the work: a sustained, slow motion improvisation that demands complete and unbroken attention.

The space as a whole is enlivened by words and ideas that are themselves in motion—spoken aloud, whispered, scrolling by on screens, or tapped out on an old telegraph. The muted and almost ghostly dialogue they create combines with the sounds of bells, breaths, and beating hearts. By speaking to the moving pictures, the sounds suggest the murky polyphony of history itself, where ideas and concepts are both forgotten and preserved. Let us imagine a straight line takes inspiration from that history. It has been my privilege to listen closely to these ideas from the past, and to respond to them directly in this work, so that they might be understood in a new way in a very different time and place.